Students at Singapore Management University (SMU), who are enrolled in the pioneering undergraduate programme at its College of Integrative Studies (CIS), have the unique opportunity to craft their own bespoke majors, tailoring their education to their individual passions and career aspirations. Choosing from over 1,000 courses across SMU’s six schools, CIS students tackle real-world challenges through interdisciplinary learning.

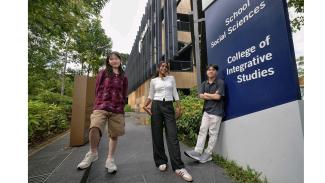

The first cohort of 44 students includes Alexander Tsai, who created a major in human-computer interfaces, blending psychology and AI, inspired by his experience during the pandemic; M.S. Sudikshaa, who is focused on environmental diplomacy, a major she designed to address her passion for climate change, where she aims to explore how international relations and policy can drive environmental action; and Raine Chiew, who combines her interest in the ethics behind advertising and marketing with the creative power of art to influence and convey ideas, with her major in ethical marketing through the arts.

SMU CIS students declare their majors only in their second year after exploring different fields. With guidance from faculty advisors, they map out unique study plans. This individualised approach allows students to develop niche expertise tailored to their passions.

While some employers may view customised degrees as lacking traditional focus, others see the value in graduates with diverse, transferable skills. Experts say the combination of interdisciplinary learning and hands-on experience, such as internships, equips these students with a unique edge in the job market.

“The end result of interdisciplinary offerings is individualised education,” said Prof Elvin Lim, Dean, CIS. “In an ideal world, every individual is unique, and we ought to honour that.”

The full story published in The Straits Times (7 October 2024) is enclosed below:

New SMU degree that allows students to define their own major welcomes its pioneer batch

SINGAPORE – Relying heavily on texting to connect with others during the Covid-19 pandemic piqued Mr Alexander Tsai’s interest in artificial intelligence (AI), sparking a passion he has carried into university.

“I am an extroverted person, and not seeing my friends during the pandemic was hard for me,” said the 22-year-old.

The experience spurred him to explore the potential of chatbots – more specifically, how AI can cause behavioural change, in the same way that chatting online alleviated his loneliness.

This led Mr Tsai to carve out his own major in human-computer interfaces at the new College of Integrative Studies (CIS) at the Singapore Management University (SMU), where he aims to study how society can integrate AI while addressing cultural and ethical barriers to technology adoption.

“I had a really clear idea of what I wanted to do,” said Mr Tsai.

He is one of 44 students in the first batch of CIS’ flagship programme – the first of its kind in Singapore that allows students to choose from several hundred courses and customise their major.

Students can select from all modules across SMU’s six schools – accountancy, business, economics, computing and information systems, law and social sciences. They will graduate with a bachelor’s degree in integrative studies after four years, with their major reflected in their qualification.

Speaking to The Straits Times, CIS dean Elvin Lim said the college champions interdisciplinary learning, drawing insights from different fields.

“The end result of interdisciplinary offerings is individualised education,” he said. “In an ideal world, every individual is unique, and we ought to honour that.”

Other local institutions like the National University of Singapore are also encouraging students to venture beyond disciplinary lines, in a push to develop a less fragmented way of learning to tackle real-world challenges.

SMU students in CIS need to declare a major only in their second year, after exploring various disciplines across the university.

They can reserve places in up to two SMU schools upon enrolment, and by the end of the first year, choose to continue in CIS under the individualised programme, join one of the reserved schools, or transfer to another SMU programme.

During this period, CIS students also take core and prerequisite modules, ensuring they remain on track with their peers should they move to another school.

Core modules, such as ethics and modes of thinking, are general courses that all SMU students must take, while prerequisites are modules that some students need to take to fulfil certain requirements for other courses.

Those who want to design their own major will, together with a faculty adviser, select modules across the university’s entire suite of about 1,000 courses and map out a study plan, Professor Lim said.

The majority, or 44, of the 62 students that CIS took in for its first cohort in academic year 2023/2024, are on this track.

“Our students are really go-getters, and many of them are already start-up founders... But you actually get both types, you get those who want to take their time to decide what they want to do.”

At times, the modules that students like Mr Tsai selects – such as psychology and computer science – appear to be worlds apart.

“While they may seem unrelated, it takes only one module to bridge them,” he said. A course like “user experience” combines the technical aspects of design with insights into consumer psychology, showing how these fields intersect.

Second-year students Raine Chiew and M.S. Sudikshaa, both 20, are also carving out their own niches.

“To be honest, I had no idea what I wanted to do,” said Ms Chiew, whose major is ethical marketing through the arts.

“I just knew that if I came to this school, I would have an extra year to try modules from different schools to see what I liked.”

An “avid consumer” herself, she was drawn to the ethics behind advertising and marketing tactics, she said, adding that she has always found the use of art in marketing to convey ideas and influence people interesting.

Still, she remains open to fine-tuning her major, owing to the flexibility that CIS offers, she said.

“I trust that if I ever reach a point where I want to make any adjustments to my major, my adviser and I will work it out together,” she added.

Similarly, while Ms Sudikshaa knew that climate change was her topic of interest, she created her major in environmental diplomacy after picking out modules from the different SMU schools.

“My first question was, ‘Would it make sense?’,” she said, adding that her initial doubts were quelled after learning about potential career paths and getting reassurance from her professors.

Are niche degrees a good idea?

It is important that students see how all their chosen modules align with one another at the end of their studies, said Prof Lim, and this can happen through the capstone project or thesis.

Some of them are already receiving internship offers in fields they are interested in.

“Students in CIS are not motivated by job security, but positive affirmations like their passions and wanting to change something about the world,” said Prof Lim.

Human resources experts told ST that customised degrees equip graduates with diverse skills, though some employers may view them as lacking the depth and focus of traditional majors.

The perception of such degrees in the job market is “difficult to predict”, said Mr Richard Bradshaw, chief executive for Asia at executive search firm Ethos BeathChapman. One concern for employers would be whether the degree has been strategically designed at a reputable institution or if it appears to be a mix of random, easy modules.

Graduates should focus on how their diverse skill sets meet market needs, said Mr Bradshaw.

Ms Betul Genc, senior vice-president and head of Asean at Adecco, said these graduates may be seen as not having a “firm mindset” on their career choice and lacking in specialised skills.

However, they do possess transferable skills – such as analytical thinking, collaboration and innovation – that should be further supported through internships and real-world experience, she added.

Mr David Blasco, country director at Randstad Singapore, said employers might value hybrid degrees, particularly if they combine foundational knowledge with industry-specific expertise.

He gave the example of a tech firm needing a public affairs professional familiar with local law and economics.

Mr Blasco said customised majors can broaden career options, as students get access to a wider network when they interact with other schools.

“The combination of diverse module options and mentorship support can equip students with a unique skill set and network, potentially making them more attractive to employers,” he said.

Photo credit: The Straits Times (ST)