Singapore, 5 September 2023 – Income Insurance Limited (Income Insurance) and Centre for Research on Successful Ageing (ROSA) at the Singapore Management University (SMU) revealed today that Singaporeans are resilient mentally, physically, socially, and financially according to a landmark study that established Singaporeans’ baseline resilience in these domains for the first time, which are pertinent findings given the context of the recent pandemic.

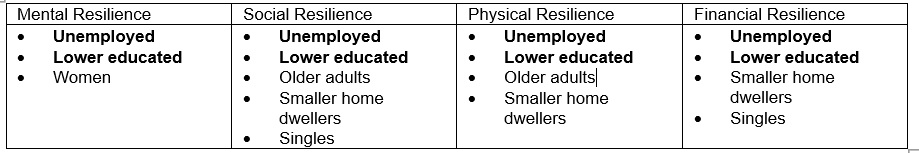

While resilience levels differ across different demographic groups[1] and resilience domains, unemployed and lower-educated Singaporeans were identified as vulnerable across all domains.

Income Insurance partnered ROSA to expand the understanding of resilience within Singapore, just as Singapore emerged from the throes of the pandemic. Earmarked as the first resilience index in Singapore, it aims to measure Singaporeans’ resilience over time, help identify vulnerabilities and help Income Insurance rally initiatives to improve Singaporeans’ overall resilience and well-being.

Andrew Yeo, Chief Executive Officer of Income Insurance, said, "Such insights are particularly pertinent especially when we continue to face challenges that stem from global economic uncertainties, an inflationary environment and geo-political tension just as we emerge from the throes of the pandemic. We have committed $100 million over 10 years to build stronger communities in Singapore. With this study, we are adopting a science-based approach to channel these investments towards resilience gaps, allowing us to lend support to truly meaningful causes and initiatives that improve our resilience in the face of uncertainties, adversities and changes that are bound to come. Thus, through continuous indexing and acting on the research findings, we aim to steward care for Singaporeans alongside like-minded partners and social stewardship programmes such as the Forward Singapore exercise.”

"The pressures that everyday Singaporeans face will continue to grow in Singapore. With this study, we have developed a multi-faceted understanding of the financial, mental, physical and social resilience levels of Singaporeans. Specific to the older adults in this study, we analysed data drawn from SMU’s Singapore Life Panel®. Intervention programmes aimed towards the development of resilience are critically important. While we may not be able to control what future challenges hold, cultivating a social environment that empowers resilience will ensure that well-being is safeguarded," added Professor Paulin Tay Straughan, Director of the Centre for ROSA, SMU.

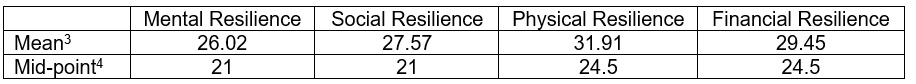

The Singapore Resilience Study examined the resilience profiles of 2,021 Singaporeans[2] aged between 26 and 78 years old. On average, the sample respondents’ resilience mean scores were 5 to 7.5 points above the midpoints of the four resilience measures, marking Singaporeans as resilient.

Other notable findings and possible reasons for differences in resilience levels identified in the Singapore Resilience Study are highlighted here:

(1) Younger Singaporeans have greater social and physical resilience than older cohorts.

Singaporeans aged 46 to 55 years old were the most socially resilient across all age bands[5], followed by those in the youngest cohort (26 to 35-year-olds). Unsurprisingly, Singaporeans who were in the oldest age group (66 to 78 years old) had the lowest physical resilience compared to those younger.

(2) Married couples have greater social and financial resilience than singles.

Married Singaporeans are likely to reside in dual-income households and benefit from their spouses’ contribution to their household income. Conversely, singles must be more self-reliant and hence, were found to be less financially resilient. Singles also reported lower social resilience than married respondents as they have access to neither the support of a spouse nor an extended family.

(3) Singaporeans who own larger housing types are more resilient.

Social, physical, and financial resilience were found to be highest amongst respondents living in private housing followed by those living in four to five-room HDB flats. The lowest levels of social, physical and financial resilience were observed in respondents living in one to three-room HDB flats. Mental resilience was not significantly different across the three housing types.

As housing types are considered a proxy for socioeconomic status (SES), it is unsurprising that those with larger homes are more likely to have higher resilience, especially financial resilience, compared to those with smaller homes. Singaporeans from higher SES are likely to have more resources to develop stronger social support networks and financial resources to cushion against risks.

(4) Employed Singaporeans have higher resilience than the unemployed, while retirees and homemakers fare better than the unemployed in social and financial resilience.

Unemployed persons reported significantly lower levels of resilience across all domains possibly due to the stressful nature of being out of work as they may face heightened financial uncertainty and health conditions that inhibit employment opportunities. Additionally, unemployment is associated with social exclusion, which potentially explains why unemployed Singaporeans reported lower social resilience than their employed counterparts, retirees, and homemakers.

(5) Singaporeans who are more educated are more resilient.

Conversely, respondents who have lower education levels[6] reported lower levels of mental, social, physical, and financial resilience. As education is also a proxy for socioeconomic status, less educated Singaporeans are likely to have fewer resources to develop resilience.

(6) Unemployed and less educated Singaporeans are the least resilient.

While we are cautious not to draw definitive conclusions about demographic differences in resilience in this inaugural study, the findings highlighted demographic groups that may be more vulnerable in each resilient domain and could benefit from interventions to improve their resilience levels.

To identify how Singaporeans’ resilience can be nurtured, the study looked at resources that constitute resilience, and found that Singaporeans who have more resources such as social support, social engagement, financial literacy, and insurance ownership, are likely more resilient.

More specifically, social support, social engagement and financial literacy are found to promote Singaporeans’ overall well-being, while they concurrently develop resilience. As these resources are widely accessible within the community, they can support interventions more sustainably.

Additionally, Singaporeans who owned more insurance policies from each insurance type – life and health insurance, wealth, and legacy planning – reported greater levels of resilience across all domains.

Among the respondents, those who are older, unemployed, women, singles and from lower socioeconomic status were found to have lower insurance coverage.

For older persons, this is likely due to the perceived onerous health underwriting process, reduced insurability of seniors and the higher cost of insurance with age. For unemployed Singaporeans, the inability to afford more forms of insurance and the lack of the employee insurance benefit are likely reasons for their lower insurance coverage.

Based on the findings above, the following suggestions on potential interventions may be considered.

- Target social support at Singaporeans who are unemployed or from lower socio-economic status. Specifically, direct support to the unemployed to ensure their overall resilience are safeguarded while they search for employment.

- Assist older Singaporeans in maintaining their physical well-being and resilience through targeted interventions.

- Include social preparations in retirement planning, in addition to financial preparedness, so that retirees remain socially engaged.

- Encourage shifts in how formal and informal work is viewed, valued, and compensated.

- Target financial literacy programmes for retirees, homemakers and those who have a lower SES. In addition, cater insurance to meet the needs of these groups including Singaporeans who are older.

Professor Straughan, said, “This study renders visible what constitutes resilience and how the various dimensions of resilience can be enhanced through meaningful interventions. We are now about to act on building resilience meaningfully and from an evidence-based perspective, observe impact of these interventions. And more significantly, this study also demonstrates that if we boost resilience in any of the four resilience domains, we can protect and advance the holistic well-being of Singaporeans.”

Shannen Fong, Vice President and Head of Strategic Communications and Sustainability of Income Insurance added: "It is our shared responsibility to build a stronger Singapore for our future generations. We are keen on collaborative efforts that pave the way for enduring positive change that empowers and uplifts Singaporeans. We welcome dialogues and actions with like-minded partners and to build an ecosystem that supports and improve our collective resilience in Singapore."

[1] Demographic groups are defined by gender, age, marital status, housing type, employment status and education level.

[2] 959 respondents were recruited from a random sample of 1,250 participants of the Singapore Life Panel and 1,062 participants were recruited from a random sample of 3,200 Singaporean households obtained from the Department of Statistics Singapore.

[3] Mean scores reflect the average scores of the sample by summing up the scores of each individual and dividing it by the number of people in the sample.

[4] Midpoint is the number between the lowest and highest possible score based on the number of questions that were fielded for each resilience domain. By comparing mean to midpoint, the respondents were found to fare better for each domain.

[5] About one fifth of respondents were in each of these five age groups – 26 to 35 years old, 36 to 45 years old, 46 to 55 years old, 56 to 65 years old and 66 to 78 years old.

[6] Respondents’ levels of education are grouped according to primary education and below, secondary, post-secondary prior to university, and university and above.